Revisioning Dialogue as Communication

over 'illuminate character, further plot, furnish information...'

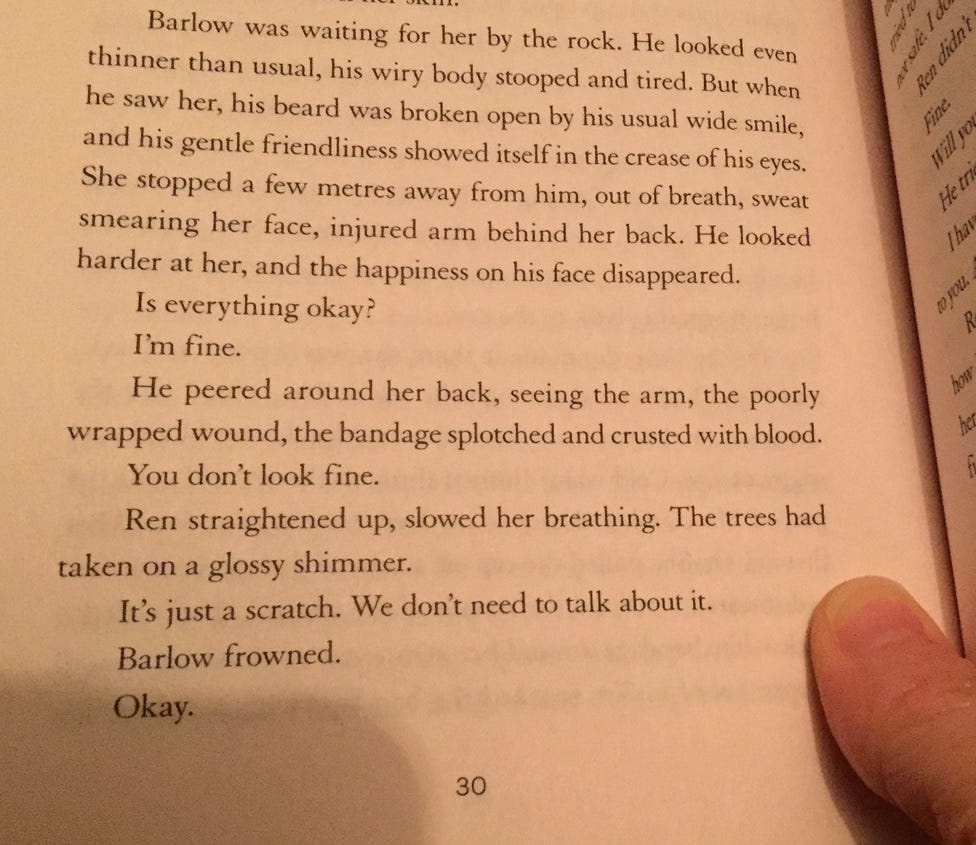

page 30 from The Rain Heron, by Australian author, Robbie Arnott

Note: I’ve taken this piece, first posted only a few months after I started The Unschool, and have added and re-shaped.

Dialogue was one of the elements of fiction I most struggled with when I began to write stories. I suspect that my struggle was the result of keeping a journal for years; there’s not a lot of dialogue in journals.

I recall one of my first night-school classes, and the assignment was to create a short exchange between two characters. In exasperation—tears, really—I wrote a poem about dialogue. And that helped to begin to break down whatever was in my way.

This “about” piece is one value in a process journal; I spent time working through the nature of my struggle. For me, it was about hearing my characters. (I may have been over-thinking this, too!) I may have been seeing dialogue too much as a plot-revealing piece. Maybe I just wasn’t there yet… but needed to be consciously opening up to including this element… which is exactly where I was.

What a thought: you may be observing exactly where you are!

The Unschooling piece

The Unschool is about learning outside of a classroom, about learning from resources we discover or even create, and learning from what is at hand. More often than not, books—the works of other writers—is what is at hand.

There’s a rhythm to learning to write, and much of that rhythm comes from the forward-backward of simultaneously working on creating pieces as whole and exploring elements of the same. Definitely an “and” thing.

Working on elements in isolation is like trying to dance by moving just your elbow.

Maybe this is why assignments such as “work on dialogue” don’t seem to do much for cumulative knowledge. The momentary focus on skill-set can seem useful, but until it’s incorporated into a whole, it’s tough to come to the kind of knowledge that’s transferable to other projects, and to how we write. How you write.

We’re constantly working with elements and wholes, one informing the other, shaping, interrogating, whether or not consciously. If you are able to write without having to share process with anyone else (that is, ‘teach writing’), then you don’t need to think this through… though this brings up a question about how writers live and work; we seem always, even those who don’t teach, to need to reflect on how we do what we do. Perhaps because there will always be some mystery to it.

As should be.

As a new-ish writer, when I was striving to deeply explore some element, I would focus. Take notes in my journal. Mull. But I learned more and more that the more I can experience within that wholeness, my understanding of the elemental pieces grew.

I also learned by oberserving other writers’ “wholeness.” So I share the above photo, a page from The Rain Heron. In this case, dialogue with no punctuation in the midst of story.

Ways of thinking about dialogue

If you’ve read the post on setting, you know I’m a trinitarian: plot, character, and setting, as the three major components of story-telling.

Often “dialogue” is said to be a close fourth. It’s supposed to illuminate character, further plot, furnish information… ooooh! beware of that last one especially. But many tout it as a must for the first two.

So it’s thought-provoking to read in Chuck Palahniuk’s book on writing, that

“dialogue is your weakest storytelling tool” (p. 14)

He’s not the first to say that 83% of communication is gesture, tone, timing; body language is the real and lasting first language we learn. One of my sons didn’t speak until one month before his third birthday, yet I don’t recall ever not knowing what he was trying to ask or tell me.

How do we include this in our ideas of “dialogue?”

Recasting as “communication” is key.

We have to consider sub-text, too: what characters (people) are really saying, the actual meaning underneath their words. The ‘What’s driving’ the communication.

While dialogue might be a weak storytelling tool, communication—said and unsaid—is a story-evoking piece—a significant one.

Another bite from The Rain Heron, by Australian writer Robbie Arnott:

Harker lifted a hand to touch softly at her bandages. This movement—this ginger graze at the site of her wound—seemed to remind them all why they were there, what their purpose was. The silence, and their journey, continued. (p. 175)

The first sentence is the gesture itself. The final and third sentence is the effect, the choices resulting from the gesture. It’s the second sentence that I linger over.

It’s a reiteration of the gesture—“this movement”—causes you to see it again, and to pause, to take time the absorb the narrator’s words, the character’s gesture, and the resultant meaning. The “ginger graze” is not expected. (This book is filled with unexpected language.) The word “wound” is an understatement; in this case, the heron has actually plucked out one of her eyeballs! The punctuation—the m-dash—pauses the thought/gesture/meaning/outcome.

The “seemed to” is solid, a piece of English subjunctive, and it allows for the reader’s interpretation. Arnott is not definitively telling you. You can interpret. The narrator is interpreting. The characters are their own people; we cannot know everything in their minds. They probably don’t. This story has its feet scrabbling at the edge of a fiction-creating cliff, always, is the sense of the thing. The “seems,” truly.

All this—these three sentences, with the most significant sandwiched—communicates much more than some bit of dialogue might. And communicates in line with what the story is.

Next time your fingers are hovering over keyboard, and you’re straining to hear what the characters are saying to each other, ask what they’re communicating? Are there words? Is it wordless? Do you want to speak to how the body language is being absorbed? Is it? Is there a disconnect between gesturer—gesture—observer?

Is the character speaking words, but the gesture is not corroborating?

Are you creating a pause for understanding? That is, not a “white space” pause, but a beat—a bit of action, words, even punctuation—some bit of slow-down?

While exploring published work for dialogue, seek instances of communication, and study.

Scanning the page

Do a visual scan of your page. Does the dialogue stand out? Eyeball it. How does it show up in your work? Is it all in one section? Is each piece/paragraph lengthy? Is one character verbose? Or do you have page after page of dense paragraphs, none of it spoken word? And what might that mean?

Is there a sense of balance to this? Does that matter? Why should it? How does it affect pacing? Check out novels you have loved reading and scan their pages.

Something else I’ve done periodically is to type out passages to gain understanding of what another writer has done. (And entire picturebooks.) The learning from this can be invaluable… though STOP the moment it begins to feel less than thoughtful, and rote.

The above photo

Take a look at the photo at the top of this post. Read and note the dialogue. There’s not one quotation mark in this novel. The dialogue doesn’t stand out to such scanning. Spoken words are spare in this work. Yet there’s never any question of what words are spoken or by whom.

The spareness would have terrified me as a new writer; I would’ve had anxiety about it being enough. I would’ve been convinced that I needed more.

And in The Rain Heron, the lack of dialogue punctuation creates an interiority, a silence of sorts. (A lack of intrusiveness?) It is a story with mythical creatures, magic realism, poetry. The choice not to use quotation marks feels to be organic. My guess is that it was more a mode that revealed itself to Arnott; it does not feel to be something he imposed on the work.

I’m always loathe to connote that a writer did not actively work—we work hard—or did not make active decisions. But if we’re in the midst of it, and open, then there are “things that happen”—either we accept them or not. Or we’ll find them alarming and back off, and go drive a cab or find ourselves behind a grocery store counter. Both places I’ve considered going, yes, but I’ve decided to live with the openness instead. The openness is the work. Terrifying as it is, it’s also enlivening.

As always, what you are saying in your story—the theme/s, the content—is so interwoven with every element, your evocation, your smallest word, yes, even your punctuation choices. One of these will inform the others. Your elbow might start the dance, but your heels with eventually move!

Writing is never just about “the story” or “the characters” or “the dialogue.” It’s the sum of many parts. How your people within the story communicate isn’t one choice; it’s a set of choices.

What they say

What they don’t say

How they say it

When they…

Where they…

And Why…

All works together. Pause with each of these, and ponder. Work through thoughts in your process journal. Return to your work, let it out on the page. All of it.

Thoughts and questions.

Great information, thanx Alsion!

Characters communicating rather than just speaking is interesting, Alison. Of course we think in terms of using gestures along with dialogue, but if you just use the idea of characters communicating, it feels like a much richer, more comprehensive approach. This just makes so much sense.