Dash it all! The En and Em Dashes

July Grammar/Punctuation Post

As requested by a subscriber. I like such requests—bring them on, please!

Disclaimer: I have far too big a soft spot for the em dash. As a result, I routinely go through my work at some later point, and CUT. (And look for ellipses, and cut half of those, too.)

But the em dash does lend a certain openness that I appreciate. Commas can get boring or worse—obtrusive—especially if you are a stickler for every last one of those little ones. And parentheses make me think of grade two. (Though I was excited about “brackets.” But that was then.)

In The Elements of Style (Strunk & White—the go-to some time ago now), their always- succinct words on the issue of dash were:

A dash is a mark of separation stonger than a comma, less formal than a colon, and more relaxed than parentheses…

Use a dash only when a more common mark of punctuation seems inadequate.

As a new writer, I tried to follow Strunk & White to the letter. But once I began to use the em dash, it seemed to me to have its own qualities of particular use to fiction writers and to evoking character voice. What works for journalism and some nonfiction, does not hold true for fiction or poetry. (Punctuation in poetry is a whole other thing, surely. Another post? Posts?)

The em dash was no doubt the beginning of my formal separation from S&W, though I’ve never filed for divorce.

Let’s start with the en dash

So called because it is the width of an uppercase “N”

It’s a simple tool to indicate passage of time, e.g. 4:00-6:00 p.m., or 1935-1972. Or from place to place: the Edmonton-Vancouver flight. Or from page number to page number: pages 4-55.

It can indicate some unknown time, such as death-not-as-yet: Sally Amiel, (1992- )

Sometimes the en dash is used to indicate hesitant or halting speech: “Y-y-you shouldn’t say that a-about m-me!”

NOTE: there are no spaces on either side of the en dash, and the same is true of the em dash. The text stays close on either side, like this—right here. Not this — right here.

And now the em dash

A bit more complicated. And the width of an uppercase M.

The em dash can happily toss the semi-colon, the comma, parentheses, even the colon. Take Strunk & White’s words and blow them up big.

Used with intent, an em dash can re-create more authentic speaking and language rhythms in dialogue and elsewhere.

Used with care, the — can take the reader away from English class and into the world of your characters.

There’s a sense of casual, even joie de vivre, to the em! Some upshot. A bit of emphasis. It can add an end piece that grows to a punch line. You can be a stand-up—for the moment.

People do not speak in “perfect” sentences. Our thoughts veer off like the last line of a good haiku, and we are away somewhere else. At least until we veer back. An em dash can make that happen, flat on paper. Amazing. Distraction illustrated with a single short line.

Or at times the opposite, and those same short lines draw us into a deeper place of knowledge about character.

Or they serve to underline some bit—some bit of “pay attention!”

Examples:

(from my work-in-progress) e.g. Was there a heaven for dogs? St. Francis—who she was named for—had thought so.

In parentheses, this added information would seem not to be coming from character or narrator, but worse—from the writer. It would turn the whole story-experience inside out. (Unless you have a reason for fourth wall.)

e.g. Not for a bag—not even a whole bag!—of gold.

Emphasis. And adds to character voice. She thinks it bears repeating.

e.g. “And look what I found—apples.”

How else could this have been written? She has not intention to allow the listener to guess. So no question mark. She is excited about her surprise. The — carries that excitement. A colon would make it too weighty. A period would be too choppy.

Often when using em dashes, play with what else you might use, and how… and you will realize why (or why not) the em dash is the right choice. Diagnosis by exclusion.

e.g. Now she closed the door quickly—she had a special skill with that—to keep out the cold air.

Those half-thoughts can pop out. In the above, it could be read as having the sense of unexpected realization. Or an insight to be shared.

e.g. At least, that’s how it felt—to be fear-worthy.

Here, too—just an added bit, popping in at the close. A bite of summary.

Or to emphasize an appositive—a noun or phrase that “renames” the noun next to it.

e.g. Feast of St. Francis Day—the Day of Blessing of Pets—was something she could celebrate in her own backyard.

A note on ellipses

Not even worthy of a glance in S&W. But maybe to aid with the thought of diagnosis by exclusion, let’s take a look.

e.g. “You mean, people are giving the books to the Bishop… for money?”

Ellipses carry the sense of weighted thought, consideration. (Or speech drifting off… )

The em dash carries spontaneity, and that openness. “Less formal” and “more relaxed”—yes, you could call it that.

Caveat:

Over-used, em dashes can become annoying. Once you are into second draft phase and read-aloud phase, be aware of them.

Also, consider who in your story gets dibs on the em.

If both narrator and a character lean on them, your character will lose their individual voice. If more than one character uses, they’ll start to sound alike. Who is the em dash person or voice in your story?

Of course—because there are always exceptions—you’ll hear this from me frequently—there may be a time when another character uses, or in the narrative there’s a place and need for the qualities we’ve discussed. But awareness! Do what serves to develop the distinctiveness in each voice.

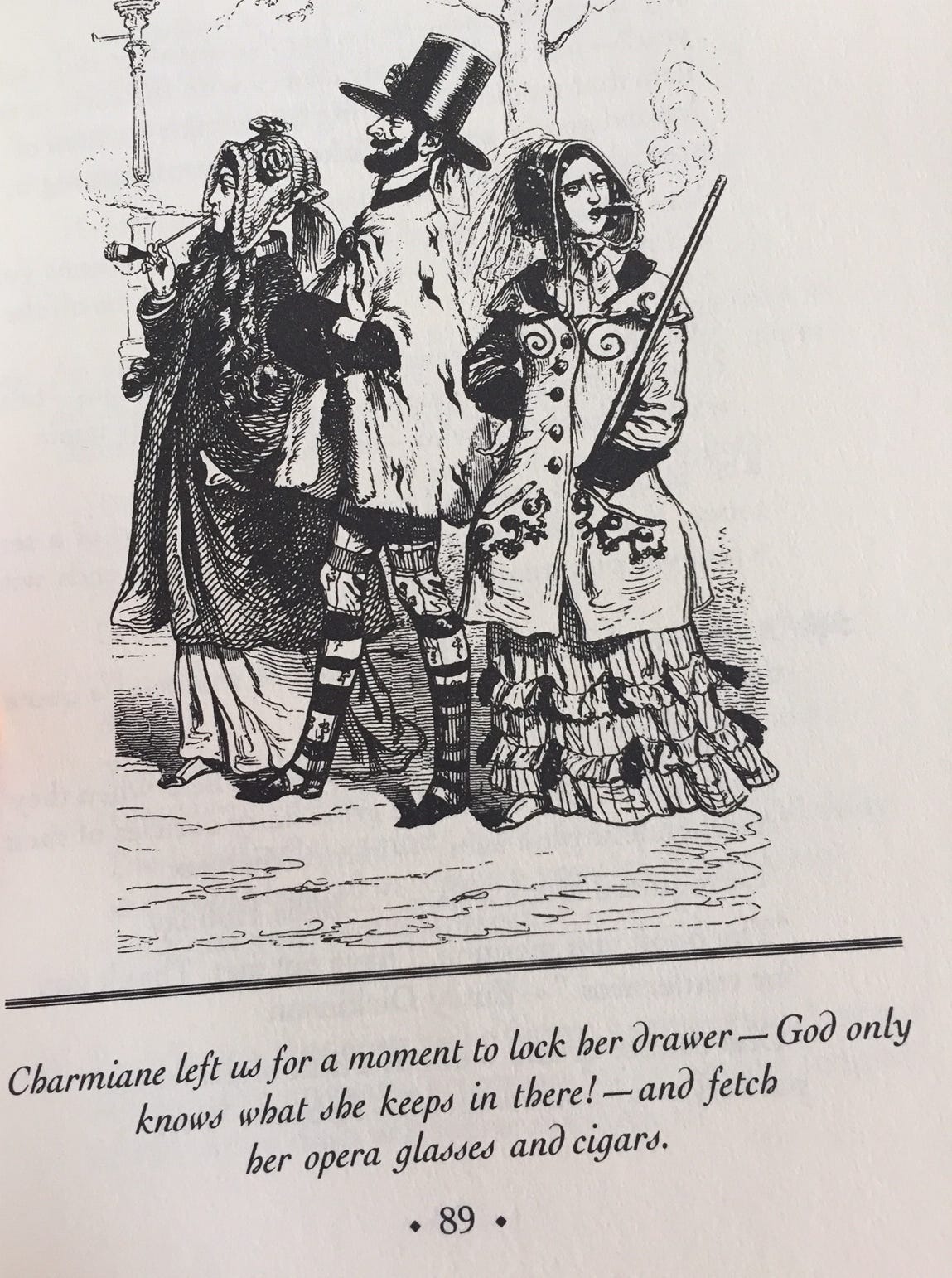

Karen Elizabeth Gordon’s, The New Well-Tempered Sentence: a Punctuation Handbook for the Innocent, the Eager and the Doomed is a wonder. Buy and study it. (Especially study the examples with the ancient woodcut drawings! Note the inclusion of an exclamation mark within the em-s here—as should be.)

What would be Gordon’s response to Strunk & White’s, “Use a dash only when a more common mark of punctuation seems inadequate”?

Maybe it should be: Cut them when you can. But use them when you should.

And double/treble em

A dash comprised of two ems indicates missing letters in a word: (with thanks to Dorothy Parker)

What fresh h——l is this?

And a dash of three ems indicates a missing word:

What fresh ——— is this?

And in these cases—missing letters or words—there are spaces on either side.

Questions?

Or post your dashing sentences in the comments. Let’s see them and share thoughts.

I came back to this today and found it very helpful. You can’t really rely on “it looks right.”

Wow! Who knew! Thank you so much for this Alison. I confused the Em and En dash(es) all the time. I hope that stops now.