Chapter 5 looks at the basic breakdown of modes of poetry: lyrical, narrative, and dramatic. In chapter 6, the beginning of Part Two, Finch begins to focus on creating poetry. It was tempting to combine, but let’s continue with one at a time. And expand with some thoughts for open discussion.

First: a note about our Poetry Workshop. Some of you have signed up for email notice, and a number have registered with the workshop space. Just a couple days ago, I posted two poems from Shirley, waiting now for feedback.

This is for paid members only, and note that anything in the workshop space is NOT to be posted to ‘Notes’ or shared in anyway, please. What happens in the workshop, stays in the workshop—always. Thanks for understanding. This is so that writers can send works out for possible publication at some point in the future, able to say that the work is previously “unpublished.”

At the end of this post, you can find “workshop instructions,” if you want to take part and know how to access.)

~~~

Last month, a writer questioned me about the academic tone of the book, A Poet’s Craft, and said that she feels as if she’s “back in school” after my last post; it doesn’t feel to be “Unschool.”

And I was not displeased she let me know her thoughts! My teaching experience has been that when one writer thinks and voices, it means there are others with similar ideas. With being online, tones and nuance can be a challenge! I’d like for The Unschool to be somewhere writers can feel free to articulate ideas and differences.

We have as much to learn, possibly more, from a forum in which we can grapple with differences of thought over posts. Finch—poet and author of A Poet’s Craft—IS an academic. Her approach is highly disciplined. And yes, her book sets up certain types of foundation before it gets close to the point of speaking to creating.

But this Unschool writer and reader brought up how she’d prefer to focus on writing, and she feels that her working time is short. She’s not young. I addressed this, in part, in one of my Q&A posts, with this conversation in mind. But many of us are short on time—with employment, children or others to care for, and all of the demands. So point taken. (Most people who have unsubscribed from The Unschool, cite “time” as their reason. Which leaves me wondering if I should post less often.)

There are some tightly focused newsletters here on Substack—ones that apply a microscope on short fiction or memoir or some one area of writing. In comparison, The Unschool is telescopic; we’re looking at the stars. You can choose a constellation and work with it, then change it up. (I’m smiling as I write that—really? Oh, why not!)

Or maybe it’s a smorgasbord; take just the salads you like. Come back for more later. If you want.

“Unschooling” is all about becoming an autodidact. Or a polymath. It’s pursuing learning—not education—in whatever way you want, in whatever direction/s you want. It’s also about absorbing only as deeply as you want.

You might read Finch’s book, but not do any of the suggested exercises. You might choose to write out a couple of the quotes she shares, and mull over them. You might skip a chapter. Or five. You might move ahead to the pages in which she write of your favourite poetic form, and focus on that.

After years of systemic education, you might want to think about the role of DE-schooling. And how the structure of “school” and “study” becomes a part of us.

My youngest son attended school until the end of grade four before he homeschooled. Then for the first year, he de-schooled. That is, we tried—as much as possible—to be free of the clock. The clock can become one’s nemesis. Or one’s friend. (Or to become ambivalent could be a goal! That old ticking thing? Whatever…) But it took years before he was “free” of thinking “recess,” “lunch,” “three o’clock.” It didn’t help that we lived within hearing of the nearby elementary school, and we could hear the howls of sports-day, and the bells and melee of noon hour each day. When he was thirteen, and suggested in early summer that he take singing lessons—early summer!—I felt a wash of recognition: summer was no longer considered “time off” from learning. Learning does not end, until you want it to. We’d progressed.

But it’s HARD to free one’s self of the clock, the exams, those pieces of paper with ticks and numbers. It’s a pattern that the average person lives with for seventeen of our most formative years. Longer with grad school.

So read Finch. Skim Finch. Toss Finch. Write poetry. Post. Ask questions. Or choose to keep your work to yourself. Whatever you do do, I suggest you always return to your own work. Ultimately, that’s what this is about. Or write a piece, and then read the chapter. Use the chapter to shed light on the work.

Again, the other part of the recent Q&A was a question asked by another writer, about revisiting and revising work or moving on. I’ll leave you to check that out if you haven’t read it already.

Back to Finch, chapter 5, and the three modes of lyrical (including the ode), dramatic, and narrative (including ballad and epic).

Like chapter 4, there’s foundational material here. It’s a bit of a history lesson in this case. The dramatic mode was intended for the theatre, really, and narrative poetry was story-telling—oral story-telling before the printing press, when rhyme and rhythm was necessary for the memorization of story sharing.

All the modes still exist, though most of what we write now is lyrical. From Finch: “Common characteristics of successful lyric [poem]s are compression and vivid intensity of image… [and] musicality.”

In other words, cut words that aren’t adding or building, or are distracting; give the reader something to “hold” in their mind or heart; read aloud for rhythm. Always. Rhythm is poetry. (Prose should have rhythm too. But can manage to make its way into the world without if the story grabs readers and holds tight. Poetry cannot be without rhythm. If you’re not sure what is rhythm, read poetry aloud. Read song lyrics aloud. )

Starting on page 439 in A Poet’s Craft, there are a small number of pages that look at ‘rhythm in free verse.’ It’s not much in all the rest of her words, surely! But it’ll give you an idea of what you can hear, and how you can hear. Interestingly, Finch doesn’t get to the subject of “rhythm” at all until Part Three of the book, page 281 and chapter 11. Read ahead if you want, if rhythm is something that leaves questions for you.

Books like this, I tend to read in parts as I need, and then read over, making it cumulative and recursive. As I read, apply to my own work, then re-read, the knowledge settles in. And I absorb as I need, discard some, re-visit, pick up again; it’s all a process.

A note about my words above on “cutting.” Do keep all drafts of your work, all scribbles. It gets messy depending on how you work. Or print and number-and-date to keep it cleaner, if that’s how you need to work. Use folders as necessary.

We can fall in love with a first draft. And that’s not a bad thing. We can push ourselves to create a minimum number. We can write twenty drafts, and return to the third when it’s time to send out to the world. But that third draft, as chosen final, might contain a word we discovered in draft eighteen, and it was just the perfect word. We know because our gut told us. And those twenty drafts were our “school.” Poetry is always an act of love more than anything. It can’t help itself. Maybe the same can be said of learning. Consider how you learn a love/r.

Finch describes how the three modes are often mixed, especially now. Dramatic monologue, with a strong and singular voice; the persona poem, with its “capacity for inspiring empathy and for expressing strong emotion.” She suggests you look through the (copious!) poems included in the volume as examples, and note how many combine these modes. This is the slow-and-read piece, the time-taking piece. Does it take too much time, or are you absorbing, and it’s worth your while?

For an exercise, she suggests that one “way to tap into the dramatic potential of your poems is to write a response to the speaker of an existing poem.”

Another suggestion, she calls “Gossip and Talk,” and suggest you invent a town or community, and write “two or more poems in the voices of people who live in the town.” They might “write about each other or about an incident that they have experienced in common. Or write two or more poems in the voices of an actual group of people you know.”

This exercise makes me think of novels-in-verse, that almost invariably are written as novels for young adults, with rather “gritty” subject material, often with multiple voices. The white space surrounding the few words on the page allow the reader to take in the intensity of the story and emotions. They truly are compressed. Check out the works of Karen Hesse as examples.

YA verse novels are often judged to be “not poetry” but cut-up prose. Check out this list in The Guardian for examples for both adult and young people. (Love that Dog, by Sharon Creech, on this list, is for ages 8-10.) The best of these works are poetic, with rhythm and thoughtful creating and shaping of lines, resonant images. Emotions are evoked and experienced. Not easy to do! They go beyond cut-up prose. For those of you still wondering about “show-don’t-tell” this might be an experiential path to more understanding.

But if poetry is new to you, or you have Post-Poetry-Class-Traumatic-Stress, take a piece of prose—your own or someone else’s—and “cut” it up. Print up multiple copies so you’re not interrupted in this, take a marker and cross out what you don’t want; mark in line cuts. You might re-write cleanly at that point. And repeat the process.

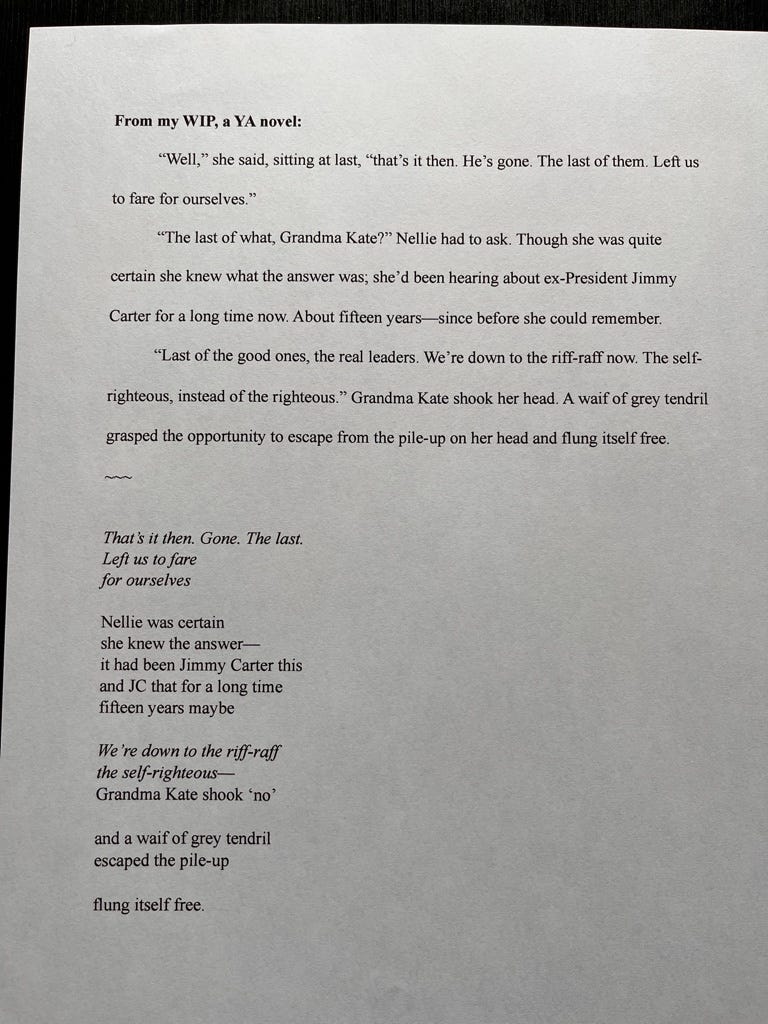

From this work, you’ll gain an understanding of Finch’s “compression” along with the rhythm that arises from choices of when and where to cut lines. Remember that your lines do not have to align to lefthand margin; they can venture out. How does spacing differently carry the meaning? I’m putting an example from my own work below.

Note that I’ve not played with moving away from lefthand margin myself in the below example. Do you see anywhere I might have?

This e.g. was scratched out from a WIP in about 10 minutes with a real sense of play. No belabouring. A good approach, at least to begin with.

I played with italics for dialogue.

I wanted an image at the close—the flinging free. The alliteration was already there in the prose. I wanted the “JC” to resonate—to demonstrate Grandma’s reverence for the man. And some idea of how these two—grandmother and -daughter—have lived.

I could continue. Feel free to post your own examples. (Alas, you can’t do photos. But write in comments, and if you do have a photo, email it to me and I’ll post in the whole.)

Part Two, in June, we’ll move into Finch’s “Making Poems: Sense and Sound.”

Leave lots of comments!

~~~

How to access and take part in the Unschool’s Workshop Space:

Accessing the Workshop Space

This is a quick update on accessing the Unschool workshop space. On your accounts page, you can opt in to our workshopping space by checking “yes” to receiving the workshop material. (You will only receive if you are a paid subscriber.) At the top of our Home page you’ll see “

And—always—an enormous THANK YOU to those who have chosen to go paid. I cannot do this without your support, and am grateful!

Alison

I guess I’m kind of old school with line breaks. I think they should be there for a reason, usually to supply a slight pause, or at least a tiny hesitation, or to create a bit of anticipation about what comes next.

Two old-school examples.

If you click the audio button next to the title, you can hear Glück read this short free-verse poem. Note how almost every line has an audible pause after it. She’s honoring her line breaks. This contributes to the hypnotic, slowed-down feel of the recitation. If you read this aloud the way you would a news article, it would take only 30 seconds instead of a full minute.

https://poets.org/poem/red-poppy-0

Song lyrics almost always have a pause at the end of each line. Here are the lyrics to an early PJ Harvey song. You could read this like a free verse poem. Like most songwriters she doesn’t use terminal punctuation. But when she sings it, there’s an end stop after every line, even the very short ones. That helps us hear all the great near rhymes and ups the drama quotient too:

https://www.shazam.com/track/10008595/man-size

(One thing we don’t get in reading the lyrics of Harvey’s songs, even aloud, is the way she often modulates the pitch and volume of her singing voice. Same with Glück’s slow-down. We really have to experience the full performance to hear those things.)

I like your example. The use of italics really helps with conciseness compared to the prose. The poem has to be read a little slower to understand, it’s really pared down, but the essential bits are there.

Jeremy Noel-Tod had a good column on line breaks last week. His first example also uses italics effectively:

https://someflowerssoon.substack.com/p/on-not-making-ends-neat

(Unfortunately italics often get lost in posted comments and e-mail and the like, so I suppose I tend not to use them.)

If we keep our eyes and ears peeled, we’ll sometimes “find” things that look or sound like poetry, perhaps accidental poetry, and with a bit of formatting can be transformed. Here’s something technologist Horace Dediu posted years ago that I had bookmarked because I found it funny, some remarks by Microsoft’s previous CEO. The first example is what I remembered, how the lines expand and contract (almost like Whitman, one might say):

http://www.asymco.com/2012/07/10/the-poetry-of-steve-ballmer/