Writing Takes Time. And Listen to the Kid

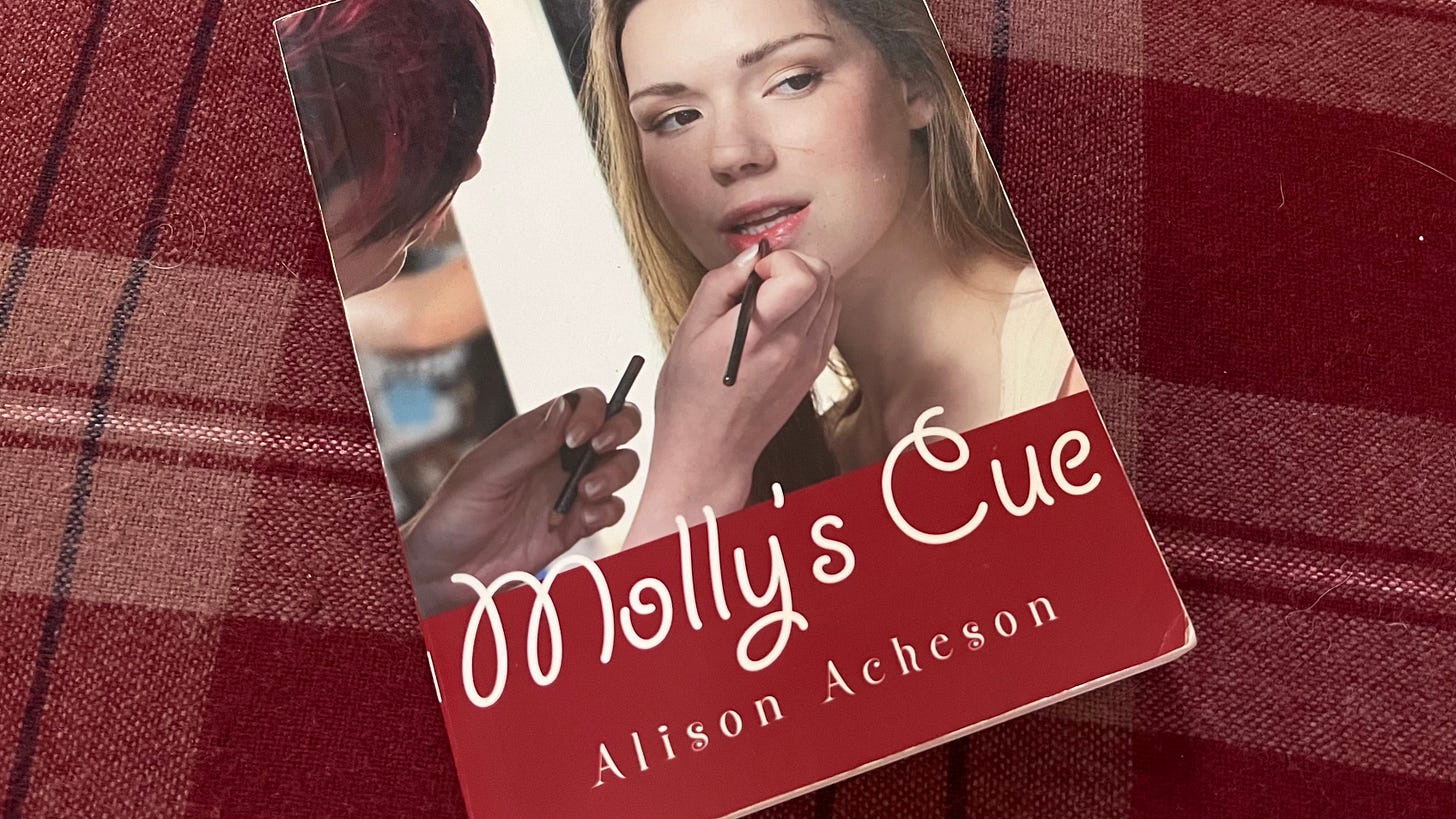

Molly's Cue: #3 in the series on my books

This is the third post in a series of lessons learned from the books I’ve published.

The other two are here:

~~~

Molly’s Cue was published in 2010. It was my fourth novel for young readers. I started writing it the year my second book was published, 1996. I worked at it on and off through all those years. I’d do yet another draft and let it sit, though never for an extended amount of time.

Do the math, and yes, that’s fourteen years.

This is a tricky one to talk about, to ascertain what might be useful for you, Unschool readers and fellow writers. I’ll share an old post about “ghost pages,” as that was a part of the process.

And the other piece: I’ll talk about the process of being handed a LONG set of comments (eight pages) from an editor at a Big Five company, working on that final re-write, and coming to a decision.

That’s where The Kid came in.

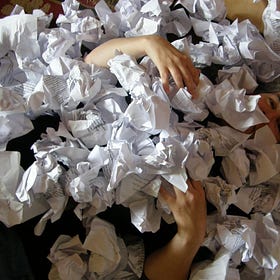

Altogether, the writing of Molly’s Cue was arduous. At one point I estimated how many pages had gone into the process. I ended up with a 250 page novel, but it took about 1400 pages to get there. I wrote this post, some time ago, looking at that.

Ghost Pages

I’d been working on my fourth novel for over a year, had just passed the mark of one hundred pages, and was feeling quite positive. Time to put to test under other eyes.

It was in the midst of writing this novel that—for the first time—I threw away over a hundred pages. It seemed like a lot. But it was a moment of real shift in my writing-life.

Within the time of creating those 1400 pages, there were complete re-writes, with different characters, exploring new themes, or reverting back to ones I’d worked with in previous drafts, though I never returned fully to any earlier draft. (That’s note-worthy.) The process went beyond what I wrote of in the Ghost Pages post. Twice, I tossed an entire draft and started over, not to look at the previous draft at all. I might have used earlier drafts to build the thing structurally; it was a form of thorough outlining. But I don’t recall using any written pages. So it grew.

Your very own MFA writing degree

I suspect many writers have such a book in them. This novel was probably the sixth I’d completed at that point, and I still had much to learn about writing. I feel as if this single book ended up accomplishing what an MFA program does for some. I played with tense and voice, plotting—from outlining to just digging into it—and so much more. I worked with adult characters and teens. Dialogue. Tension and pacing.

At a number of points I just wanted to toss it, and give up on the subject matter: stage-fright, fear of creating, all the ways that adults make a mess of things and expect kids to carry on…

At last it went to my agent, Irene, an experienced New Yorker, in the biz a long time. I worked with her for the time before she retired. She had a wonderfully gentle insistence to her.

She sent it out to a handful of editors who might be a fit. And one, at HarperCollins US, came back to her with no less than EIGHT pages of single-spaced thoughts and suggestions.

And here was the rub

The main character—Molly—had a beloved hippie uncle named Early, and he was pivotal to the story. Or at least, as I saw it! But that wasn’t how this editor saw it. She wanted him gone.

To take out Uncle Early would mean having a story filled almost entirely with female characters, and would feel off balance to me (having grown up with three brothers and raised three sons). I had to re-create family.

There were many other changes she wanted.

At that point, I hadn’t sold a work to a company of size, for an advance that would cover a rent cheque. And this was HarperCollins! I had to try.

It took a solid six months of work. I worked on no other project, and focused on making the changes to the best of my ability.

Then there was a time of reckoning. I remember slowly reading through the “original”—if I can call it that after 1400 pages. Then reading through the new draft.

I felt miserable. I’d put 100% into this latest. It was a good book. But… it wasn’t my story.

Bring on the kid

In spite of all my years of writing for children and young people, I’ve never asked for a young reader’s input. I think of Robert Munsch, who worked at a pre-school for years, and read his work to the children, and paid attention to their feedback—laughter and excitement. Or dull stares. (With Munsch? Surely not.)

At the time, I had a fourteen year old neighbour who babysat my sons, read Russian novels, was thoughtful… and wanted to be a writer.

I asked her if she would consider reading the two versions, and only told her that “one an editor had requested, and the other, my agent liked…” because, in spite of her reticence to speak up, I suspected my agent was not on board with those eight pages.

Stephanie read the two versions and handed them back to me. She said—as might be expected of a fourteen-year-old, even an articulate and well-read one— “I like them both.” But she added, “I don’t know why you cut out that Uncle Early character, though! I like him!”

She’d confirmed my thoughts. My gut settled in a way I needed to pay attention to.

Only when I told Irene that I was making the decision not to send on the manuscript to the editor, did she let loose with her thoughts about those eight pages, how they crossed all sorts of lines, to her mind; how she was quite fed up with this editor… and so on. Should she have let me know before I spent all those months working this book yet again?

No.

I needed to do what I did.

Would my writing career have been different if I’d gone ahead and sent the manuscript anyway?

For a long time, I wondered about this, and felt it was quite possible. There’s the lure of the Big Publishers, and all that means in terms of distribution, reviews, being seen differently.

But as time has passed, I’ve come to think “probably not.” In all the re-writes-for-editors I’ve done—too many to count—I’ve come to know to only go ahead with such a request if it is to my benefit, if I know it will strengthen MY story, and not change it fundamentally.

Editors’ comments can be precious. They can also be something that has nothing to do with me or you. It took me time to learn the difference.

For the record: Thanks, Stephanie, wherever you are.

Irene retired. I submitted the book to Coteau, who had published my first three middle-grade and YA novels.

And Uncle Early lived on.

Oh yes, always listen to the kid! My editor often didn't like the way my main character spoke. She would say, "Kids don't talk like that." And, perhaps the kids she knew didn't. But I was using words and phrases I heard from kids in my life!

Long, long ago one of my scripts was a winner in the Atlantic Film Festival's Scripts Out Loud. We 4 winners workshopped our pieces with a highly-respected instructor. He suggested so many changes to my story, though claiming to like it, that by the end of the process I didn't feel I had any connection to it. It was just another script. I never did much with it after that.