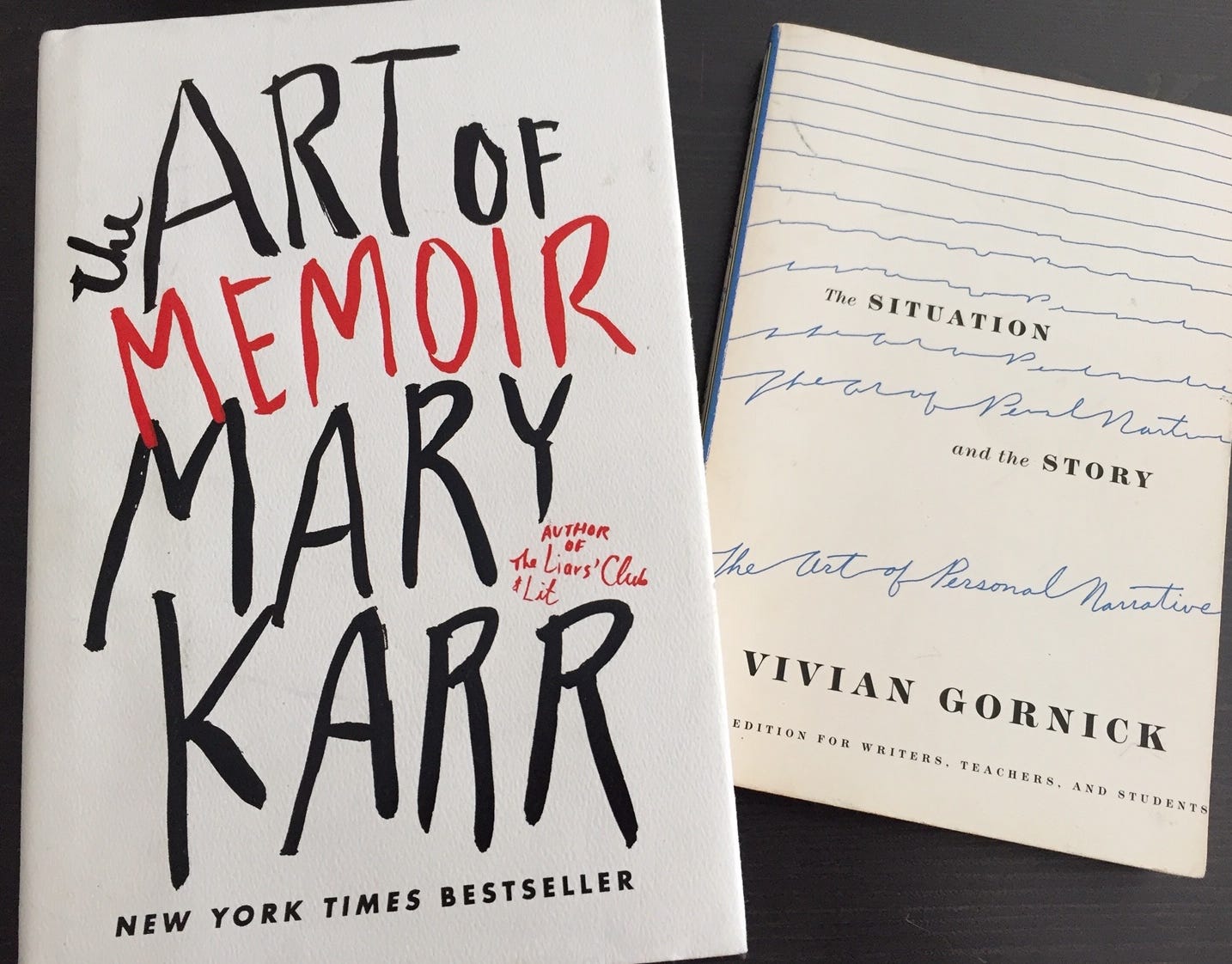

In the early days of writing my memoir, Dance Me to the End: Ten Months and Ten Days with ALS, I sought out books about the genre. These were the two that I read more than once, underlined, scribbled notes... Pages are falling out of the Gornick paperback!

Even if you write fiction

Consider studying what it means to write memoir; to create and write fictional characters is to seek to understand what it is to be human. Thinking about “memoir”—the writing of self and persona—can serve to bring truth to your work.

Vivian Gornick’s, The Situation and the Story, breaks down the narrative of memoir into these two strands. Gornick defines situation as “the context or circumstance, sometimes the plot” and the story is “the emotional experience that preoccupies the writer: the insight, the wisdom, the thing one has come to say.” Gornick speaks to how the writer writing autobiography is defining the self and too often the self feels to be in a void; the memoir-writer must engage with the world—that engagement/connection creates experience, and experience brings wisdom—or “the movement towards it.”

Journalism to 2. essay to 3. memoir… each steps ventures more deeply inward.

The writer of memoir must fully realize a “persona”—and “to fashion a persona out of one’s own undisguised self is no easy thing.”

“The unsurrogated narrator has the monumental task of transforming low-level self-interest into the kind of detached empathy required of a piece of writing that is to be of value to the disinterested reader.” (page 7—my emphasis)

What follows is a guide to understanding the qualities of “persona.”

For me, this brought a certain freedom. I did not want to devolve the telling of my months of caregiving into “self-interest.” That was what my journal pages were. (And ugly pages, indeed—for my eyes only. Not because of “privacy,” but filled with moment to moment self-pity, questioning, messiness. Life being lived with little time for reflection!)

What I needed—desperately—was to locate and write from a place of “detached empathy.” The word “detached” is cold, but speaks to distance... maybe I should call it “empathy-with-time-added.” (Karr says one needs a minimum of 7-8 years after a time, to write of it.)

Detached empathy

Whatever we call it, those two words refused to dance together for me for some time in the writing. As I was working, I frequently stopped to read my under-linings and scribbling in both of these books. A few paragraphs at times, some bit of reflection written, maybe a walk to absorb the idea… and then back to work. Exploring the persona was the path; I could not leap from where I was—described above—to “detached empathy.” I had to find Gornick’s “truth-seeker.” The “narrator that a writer pulls out of his or her own agitated and boring self to organize a piece of experience.” (And yes, it can be called “boring” to read about someone’s painful minutiae—check out Joyce Carol Oates’ A Widow’s Story, if you want to feel it… I did not want to write one of those. After reading a number of such books, I began to think that editors might be terrified to touch them. A result of the subject matter? The status of the writer? Sometimes editors have to lose fear… they have a most particular task. I digress.)

Gornick says the work will be strengthened by the knowledge of who you are at the moment of telling. As I worked through my writing, I was constantly interrogating this: who am I now, in this moment? Who was I in the midst of the experience? This creates a dynamic, one I needed. It pushed me to dig deeply. (And freed me, too; there is that!)

Gornick says that it is this “struggle to clarify one’s own formative experience… the strength and beauty of the writing lie in the power of concentration with which this insight is pursued, and made to become the writer’s organizing principle. That principle at work is what makes a memoir literature rather than testament.” (My emphasis—and see note at close.)

Gornick has thoughts about the paths taken by modern and postmodern fiction, as well as memoir/nonfiction. The “preoccupation with human isolation that has been growing steadily over the past hundred years.” Decades ago, “people who thought they had a story to tell sat down to write a novel. Today they sit down to write a memoir.”

This questioning is both significant to the book as a whole—yet another good reason to read!—and it also intrinsically connects with her focus on the dynamism of thorough exploration: writer pushing at persona. Mining deeply.

“That impulse—to tell a tale rich in context, alive to situation, shot through with event and perspective—is as strong in human beings as the need to eat food and breathe air.”

Again, solid reason for fiction writers to take a long look at this.

Closing quote from Gornick:

“Truth in a memoir is achieved… when the reader comes to believe that the writer is working hard to engage with the experience at hand… what matters is the large sense that the writer is able to make of what happened.”

Art of Memoir

Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, is gold. I’ve read it multiple times; every time I draw another layer from it. (And her The Liars’ Club is more gold.)

Her advice to complete a first draft in order to have some understanding of what the work is saying, is how I write fiction. It can be reassuring to see your own choices reflected on occasion… even as we try the new and grow. It means work and tossing, but Karr writes many many drafts.

Carnality

There’s a concreteness to Karr’s thinking, her suggestions: start with events, draw meaning from events. There is a physicality she is driving for, that she evokes and promotes. She describes stories as having “geography.” She uses the word “carnality” for what every story needs (“sensory impressions”) and expects you to use it until the “reader gets zipped into your skin” (love that phrase!) I think of carnality, too, as being able to take hold of ideas/story in mental hands, making it palpable.

Karr has a significant piece in her thoughts on how far one can push the “truth” in memoir-writing; she has a sizable bone to pick with Gornick here — too much to discuss in this post (!), but suffice to say that Gornick has been quoted: “I embellish stories all the time… I don’t owe anybody the actuality…” Gornick has been taken to task on this elsewhere. You can look it up, if you insist—her book remains thoroughly useful to my mind. But I think there is deep truth to Karr’s thought that “inventing stuff… fences the memoirist off from the deeper truths that only surface in draft five or ten or twenty.” The writer will be “missing the personal liberation that comes from the examined life.” Yes.

Karr urges writers to admit to when memory is blurry. There are artful ways to do this: the “best ones openly confess the nature of their corruption.” So if you are hesitant to venture into memoir—and possibly writing a story that has meaning for you—because you do not trust your memory to be exact, then consider reading Karr, for how to deal with such limitations, and still hold to what is valuable. She deals with questions of re-creating dialogue, and real, and living, humans as characters. About interpretation, she says, “be generous and fair when you can; when you can’t, admit your disaffinity.”

“However random or episodic a book seems, a blazing psychic struggle holds it together, either thematically or in the way a plot would keep a novel rolling forward.”

She includes a list of reasons why you shouldn’t write a memoir; it’s a good list. And a chapter titled, “Dealing with Beloveds (On and Off the Page).” The first list gave me food for thought, and strengthened my spine, and the second prepared me for what-was-to-come, an aspect of nonfiction.

Gornick and Karr speak of the compassion needed—often to keep rage or blame at bay—in writing memoir. And both writers speak to the need—need—to understand why you are writing the story you are.

And the Unchooling piece…? These books will leave you with a list of some of the strongest and most enduring of memoirs to read. (Karr’s has an appendix to check out.) I bought many of these, and read one after the other, to create my own study of memoir.

*organizing principle — this is a significant piece of nonfiction writing—any writing, really. It’s a fishing net. Without, you can catch a lone fish, but to bring it all together, to draw in enough to feed, you need a net. The post about content and form says something about this, too.

And: “people who thought they had a story to tell sat down to write a novel. Today they sit down to write a memoir.” What are your thoughts on this?