It’s easy to toss a line or two of lyrics into a story to illuminate character or set a tone, just a phrase or two here and there for flavor.

Let’s say the story is accepted (of course it is!) and about to go to print… when your editor asks about the paperwork for the rights for their files. Oops!

Things to know: it is the author’s responsibility to secure the rights to use song lyrics

It is also—unfortunately—the author’s responsibility to pay for those rights. This means that you might want to reconsider using certain artists’ works.

For instance, Bryan Adams charges a small fortune (by writer standards) for the use of even a phrase; Bruce Springsteen, on the other hand, a next-to-nothing, nominal fee. (Artist with a heart.)

You also want this information — the cost — before you sign a contract with a publisher; you might be able to negotiate with the publisher to take on at least some of the expense, as it can add up. Especially if you’ve included multiple lyrics.

In my most recent book contract, I managed to negotiate half of the costs. I’ve gotten braver over the years. One other time I had to do this I paid all—several hundred dollars for two lines of a 1972 hit no one’s ever heard of: “Beautiful Sunday.” (We sang the song in my grades two and three classroom, and the lyrics were imprinted… what can I say!) And another time, I used the public domain song, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

* Here, I’ll digress! See “the story” at the end of this post.

Large companies oversee the administration of licensing rights. I have included links to some of the larger ones to get started. Do NOT go to the artist’s site or try to contact them! (There may be exception to this, with community/friend musicians.)

Weigh it up

How badly do you need to use the lyrics? Can you come up with some of your own for the purposes of the story? What about using lyrics that are within “public domain”? That is, older works prior to January 1, 1923.

(Be aware, though, that some of the more popular old works will have had heirs renew copyright, so you will still need to do a bit of research.)

I used “Dance Me to the End” — from the Leonard Cohen song — as both my memoir title and several lines of lyrics within my manuscript. Really, I could probably have gotten away with not including the lines. I scrutinized that portion of the text, wondered if I could get away with just mentioning the title and how “I heard the song on the radio “— without the actual lyrics . Maybe that would be enough. Perhaps the reader was already familiar with the song, or curious enough to go look it up.

In the end, though, I decided that the story itself really did require those words right there on the page to keep the reader with my story. What will be the loss for the readers if you tiptoe around this? Is it worth it?

I decided the words were integral.

Note: titles are not copyrighted.

Next step

After deciding that I did need the lyrics I went to the Hal Leonard site. This is the company that oversees much licensing. You are likely to find your title here. The linked page takes you directly to the “request” page — you can see what it looks like. This process used to take months — six months, in fact, the first time I had to request lyrics rights. But now all is online, and you can feel safe allowing 2–3 weeks for the process to be complete. (Note, some sites say 4–6 weeks.)

Alfred Music is another go-to site, if you can’t find a title at Hal Leonard. You can also try BMI or SOCAN (Canadian) as a way to track copyright.

If you still cannot find your title, find online lyrics or sheet music, and look for words about who holds the copyright. A bit of sleuthing, and you should be fine. I found people really helpful with this process — you can ask someone from one of the above links.

They are pleased that artists/writers are honoring the copyright system.

Information you will need to share

Once filling out the online form, be prepared:

book title, publisher name and address

when the book will be released

exactly what words you want to include, the (approximate) page number on which they will appear (this can be a bit of a challenge before it is in print—you might have to ask your publisher to help), and the context

where the work will be distributed (the rights your publisher has purchased)

the retail price and number of copies for the first print run

Note that once all the paperwork is done, you will be given standard wording to include in your book to acknowledge your right to include in your work — your publisher will know how to deal with this.

Step by step, you will be informed of the costs and what rights you are purchasing, for how many copies. Most will accept credit card payment, though I have had to pay one with an international money order. Keep all your paperwork to pass along to your publisher, with copies for your own records, of course.

Sometimes people get away with things…

You are going to stumble over books with quoted words in which there are no acknowledgements. Yes, some people get away with this! And even sleep soundly.

Imagine if your book takes off, thousands of copies flying off bookstore shelves… and someone realizes you’ve quoted and not asked for permissions, and your book is recalled and pulped… (what is pulped? as ugly as it sounds.) Altogether, not a good scenario. And there is that sleeping thing and conscience; I like sleep.

As artists, we all know the significance of copyright.

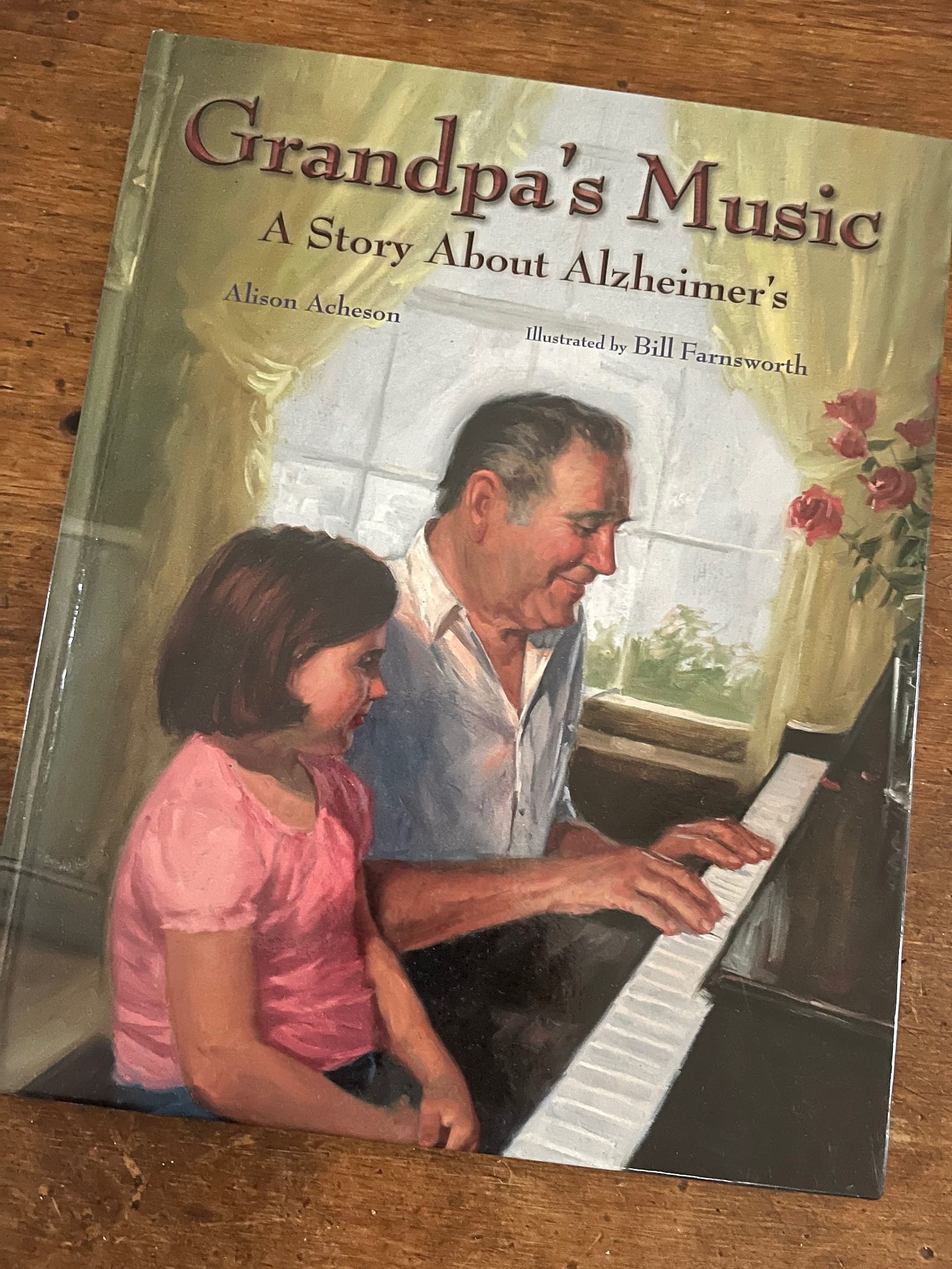

* the story about Grandpa’s Music: A Story About Alzheimer’s — or a story of including song lyrics!

In my picturebook story about a child living with a grandparent who is in early stages of dementia (published with Albert Whitman & Company, 2009), I focused on song lyrics and music and memory.

After seeing several manuscripts from me, a senior editor asked me if I might have a story about Alzheimer’s. Editors are amazing people—they have elephant memories, truly. ALWAYS treat any communication you have with them as Stuff They Will Remember… Forever. Because they do.

If you have unprofessional slips, they’ll remember that, too. Be professional, work hard, show them your work, show them that you can work. And build each relationship.

This editor liked my work enough to ask me for something specific, even though to that point the mss. (manuscripts) I’d sent her did not work for the company as a whole.

I resisted the idea at first, as the subject matter terrified me—frankly. But found a way into the subject after speaking with my sister-in-law about the two years when her father lived with their family, and how my nieces, aged 3 and 5, lived with that reality.

I also did some research about dementia, which brought me to “music” as a theme that resonated for me. (I found some work that people were doing, that focused on the idea of going into new and created places as opposed to the torment of trying to “remember.” And I read every published picturebook I could find on the topic (all of which focused on exactly that... the torment of memory!) I wanted a new direction.

I came up with Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World” for a song to include, and (and here is the Problem!), the closing line of the story—the most challenging part of creating a picturebook—worked with the song. So I had this for my closing lines:

Grandpa sees the piano. He sits and stares at the keys.

He begins to hum, and I sit beside him.

“Do you remember the words?” I ask.

“The words?” he says. He plays a few notes softly, and they’re not quite right.

“We can make up some words,” I remind him.

“Yes,” says Grandpa. “Let’s make up some words. It’ll still be a wonderful world.”

I researched the cost for copyright, and conferred with the publisher, and it was all going to cost quite a bit. I was urged to find something in public domain.

After a lot of lyric reading and digging about, I found a song, popular in the era of WWI, and re-wrote the ending of the story. (Yes, it was a lot of work.)

So then I had:

Long Long Trail A-winding

Grandpa sees the piano. He sits and stares at the keys.

He begins to hum, and I sit beside him.

“Do you remember the words?” I ask.

He plays a few notes.

“We can make up words,” I remind him.

“Yes,” says Grandpa. “Let’s make up some words. About the trail, Callie, right? I like our trail.”

“I like our trail, too, Grandpa.”

And the publisher came back to me with the thought that the song was too obscure. Could I come up with something else, they wanted to know. One of the people in the company suggested “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” a suggestion which, after all my work trying to find something that worked, rather deflated me.

So this is one of those posts that, in addition to being a “how-to negotiate lyric copywright” also has something to share about working with editors/publishing, AND how to stay open in our work. At that point, I was reminding myself of that hourly. I thought that that ubiquitous song had nothing left for me. BUT I went ahead and decided to work with it anyway. Sometimes—often—I cannot work through ideas in my head. I have to apply myself to working on paper, with words.

I began with reviewing the lyrics to the song, and tried to look with fresh eyes. I thought about the research I’d been doing—the thought to come up with “new” from “old”… well, that was exactly what was going on here, I realized.

And then I realized how my brother’s family had worked with their dad and father-inlaw and beloved grandfather… exactly as a team. I remember feeling teary after that thought came to me. I wrote. I played with those lyrics. I re-wrote the end. And in the end, I realized that “Take Me Out…” was in fact the best choice. It added that “team” element that I’d been feeling but had not, to that point, come out in the story itself.

The bonuses of meeting the publishing folks’ asks, and then the fact that the song is most definitely “public domain” and would cost nothing and save me time and paperwork… well, it was win-win in a most unexpected way.

For me, the fact that it created the best closing line of all three songs I’d worked with—even after weeks more and hours of work—was the ultimate “win.”

Lessons? Keep an open mind! and be willing to PLAY. Dive in and try, before saying “no.”

In the end, it was:

Take Me Out to the Ballgame

Grandpa sees the piano. He sits and stares at the keys.

He begins to hum, and I sit beside him.

“We can make up words,” I remind him.

He plays a few notes. “What about the home team?” asks Grandpa.

“The song says, ‘If they don’t win it’s a shame’.”

Grandpa shakes his head. “I’ve never liked that part. But I sure like going to

the game—maybe we can sing about that.”

“We can sing about that!” I say.

If you want to see the picturebook, for the whole story, you should be able to find it in your local library, exactly where such a book should be about this subject. It is now OOP (out of print), but you can find it there.

Thoughts? Questions?

This reminds me a little story told by the composer Gordon Goodwin. He dropped by the studio one day where they were recording the soundtrack of a big space movie. He, and only he, noted the similarities between the music that is being recorded and Stairway to Heaven. He pointed this out and producers said they would fix it later. “Fix it” turned out to be burying it, or trying to, under a bunch of special effects and explosions in a climactic space battle.

This did not, however, escape the notice of Mr. Zeppelin and a cheque was written in due course.