Q&A: Bringing nonfiction technique to fiction

What does this look like?

I’m continuing to work with your questions. This one, from Terry Freedman, who writes…

Terry’s question:

I like to use fiction techniques in my nonfiction writing, but do you think there are nonfiction techniques that could be used in fiction?

~~~

Strong, resonant fiction has verisimilitude. That is, slips of “real” that create believability. Whereas nonfiction might use colourful language and metaphor—borrowed from fiction and poetry, but in truth, it’s awareness and strong writing—fiction is strengthened with breadcrumbs of real.

How?

As much as I recommend Robert McKee’s tome (Story) on screen-writing for knowledge of fictional story-writing, I have to add Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir to the list. I had a revisit, while thinking about this question; studying other forms is always useful. Memoir-thinking for fiction; creative nonfiction technique for fiction.

I mull over my own work, post writing nonfiction: what has that work brought to my imagination? Lines blur—nonfiction, memoir. Borrow. Or steal.

Starting places

Karr speaks of Don DeLillo saying that fiction begins with meaning, and the writer then creates events to “represent it.” The memoirist or essay-writer can begin with events, and pull meaning from them.

Fiction, for me, often starts with a question that’s really messing with my head or gut (“meaning”), but there’s no reason it can’t start with an event. If you look back at the question I was working with a few weeks ago, about “ideas,” an “event” (think “situation”) could serve to get a fictional story off the ground, yes. (If not currently working with a project, but in search of ideas, jot any events/situations that come to mind or that you hear of into your process journal. Writers are gleaners; we are always listening for story ideas.)

Writing nonfiction can—should—teach us to question. Writing memoir teaches us humility; it can’t not. And humility is a gift to the work that is writing; it gives us room to poke around. It lends a certain quiet to the task of creating. Humility is openness; openness is seeing anew.

These are all pieces of the writing process. (Ego has a place, too, but more on that later.)

Karr speaks of the “detached, watcher self.” I am very familiar with this: when my spouse was ill and I was caregiving and scratching out a couple of journal pages every day to have tenuous hold on some form of sanity, I was aware of this part of myself. Often I wondered how non-artists cope with traumatic times—how do they express and feel their way in and through? (As I wondered if I was getting “through.”)

But for the purposes of fiction, to have a part of self that can detach and observe might be key. Not so much during the hours of physically writing, but the other times—long walks, folding laundry—times of Thinking.

Karr questions, “Who IS this person?” And she says, “You want to get next to that quiet, noticer self as starting place.” (Love the word “noticer.”)

An excellent approach for memoir, it’s also useful in fiction. You can inhabit this character, this persona, who might possibly be the narrator (whether or not the narrator is an obvious character, or some off-stage yarn-spinner). Detachment can be useful.

And know that this detachment is temporary; that “detachment”—that noticer—is actually Real You. It just takes time to quiet the noisier one rattling away on the keys.

The elementary classroom

Do you remember the language you were taught in grade school around writing stories, or reading them? “Protagonist” and “antagonist?” “Primary and secondary” characters. “Round” and “flat”… if a teacher was really into it and had done a little study of the subject.

When you write memoir, you consider the need for generosity in how you bring other “characters”—people—to life for the reader. Your biases (“antagonist”) can be heavy-handed; you need to step back. If you bring this same approach to your fiction, your stories will be richer and more nuanced.

“Generosity” while writing all forms of nonfiction will cause you to take adequate responsibility for “getting the story right.”

Think: what is the other side of this?

*(Incidentally, in Karr’s book she has a chapter devoted to why you shouldn’t write memoir—worth a read, if you have any question at all… and maybe you’ll find an answer as to why you should be writing fiction.)

The real

Karr calls it “carnal”—the physical reality of story-telling. But setting—place and details, from “where,” to how the sun looks setting in that place—should be alive in your mind. As real in fiction as you work to evoke for nonfiction. The real will leak through. So take the time to place yourself.

Often a carnal/physical detail noted in my journal, in my mind, will evoke an entire memory/story. This doesn’t have to be any different in fiction. You know: the ‘pay attention’ thing I tend to go on about.

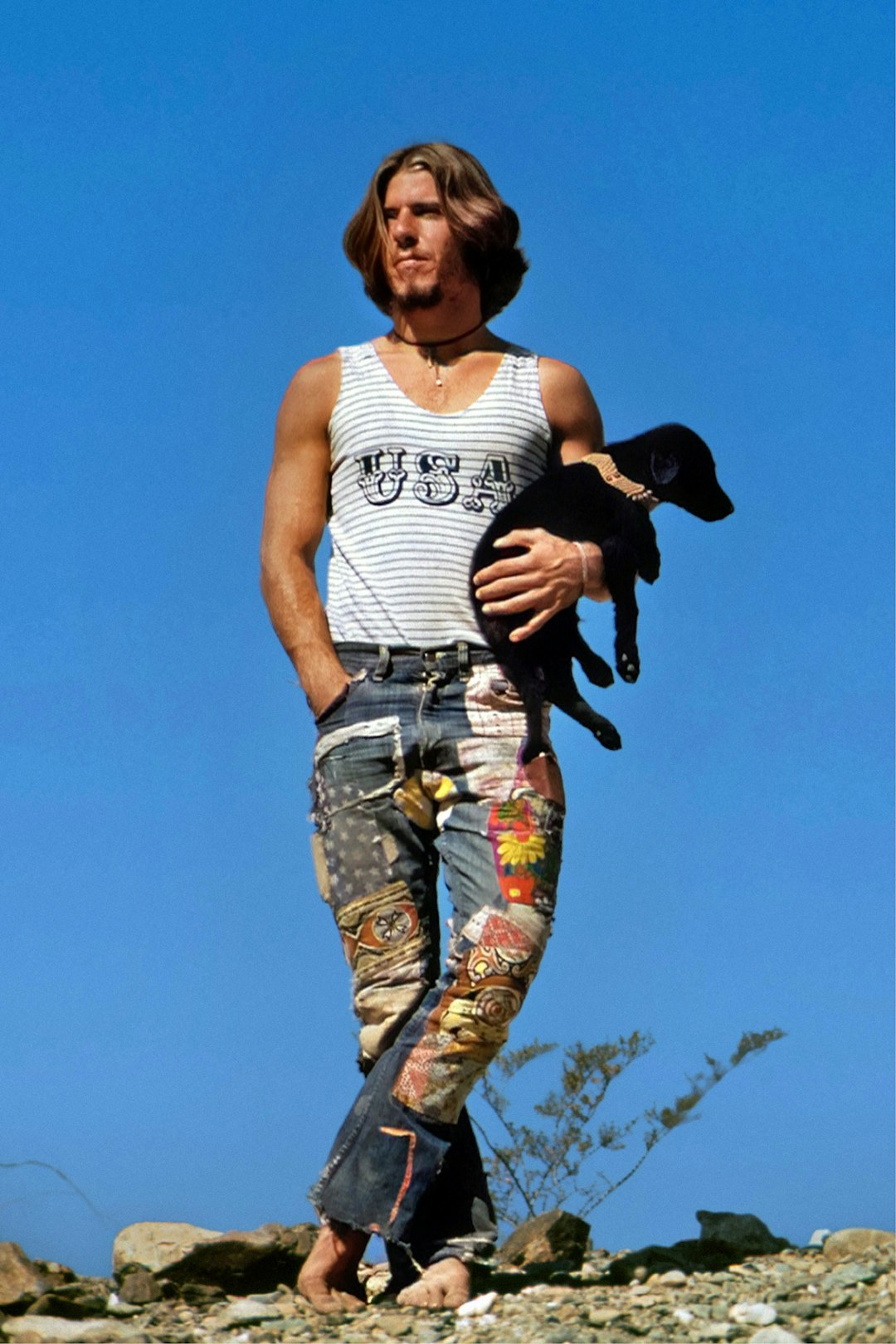

You’re more likely to describe something memorable about a person in nonfiction. Readers often have strong (negative or positive) feelings about physical description in a story, and often writers leave it out when it wouldn’t occur to them to do this in nonfiction. Why?

Karr says that the reader needs to “get zipped into your skin.” Yes.

For fiction, readers want to get zipped in with the characters.

Approach

Many writers bring a certain attitude or approach to nonfiction. How does this serve your writing, and can you change up how you approach one and then another form?

We want to get at the truth of the thing. Fiction is rich with truth; it’s only presented differently. You won’t have to defend it in a court, but you should know this fictional truth in your gut. The phrase “this could have happened” should come to mind, and can affirm why you’ve made certain choices.

That idea of “truth being stranger than fiction….” The most bizarre stuff can happen in “real life,” and we hesitate to place it in fiction. We say, “If that happened in my novel, no one would believe it.” But it can be exactly such moments/scenes/character- qualities and more, that create a story readers enjoy. It’s more about setting it up as believable, and creating the emotional space in your reader for them to be caught up.

Go ahead and write it however you can. Get it on paper, and don’t censor yourself. Then play with it—re-write in multiple ways. You might need to set up some earlier idiosynsrasy in a character. You might want to work with the language choices you are making to build a setting of possibility. Consider: what would cause you to buy in?

When you are reading fictional works in which the almost-unbelievable happens—yet you find yourself believing—read, enjoy, then return for an unpacking. How is it you came to be invested in the story? What did the writer do, what did the characters do?

Emotional stakes

Is a phrase that Karr uses to describe the investment a writer has in their work. Why would you not have emotional stakes in your fiction? She says that what holds a memoir together is a “blazing psychic struggle.”

The best fiction, the stuff we remember and have nightmares and dreams of, surely it too has “blazing psychic struggle.”

I’ll leave you with some of her words:

“… have more curiosity about possible forms the work could take than sense of self-protection for your ego.”

In other words, go bravely to play and connect.

~~~

Other posts in this Q&A collection:

Q&A: Joan's question about second draft and "flow"

A couple days ago, I responded to the April Poll results by asking for QUESTIONS. There are now several posted. Please add yours to that post! I’ll start with the first, from Joan, who has recently completed the first draft of a lengthy work: When I am inserting a new scene or chapter into a second draft novel how do I do it without disturbing the flow of the story? I guess I am asking about the transition points?

Q&A: Jordan's Question - IDEAS

Continuing to work with your Questions! From Jordan: I’ve been writing short essays on my Rocky Point Substack. Do you have any tips for ways I can switch my non-fiction, observational mind into a fiction engine that can create short stories and novels? Plot ideas escape me. Thanks!

I would add journalism to the list. It’s probably no accident that a lot of novelists started out as journalists: Hemingway, Joan Didion, Robertson Davies, Charles Portis (author of True Grit), so the reporter’s basic who-what-when-where-why is something you can sometimes see in their work.

Of course, journalistic precision and clarity isn’t right for every style. For example, Kafka’s stories almost never mention real place names or people or dates. That gives his work a kind of vagueness, but almost maybe a universality that specifics might undermine.

I think one journalistic thing to avoid is the New Yorker / Guardian / New York Times “profile” approach to description. These articles are really just celebrity puff pieces. You can tell when you’re in profile territory by the tics, for example always describing like a fashion magazine what the profiled person is eating or drinking (“grains, seeds, black coffee”) and their appearance and how they’re dressed (“Eggers, who is thirty-eight, has pale-green eyes, a dark cropped beard, and hair buzzed close to his scalp on the sides. He dresses in black, and his left hand is heavy with signet rings and a large gold watch.”). This is probably okay for parody or satire, but readers might find it tedious otherwise.

The two quotes that resonated with me were: "Writers are gleaners; we are always listening for story ideas." and "That idea of “truth being stranger than fiction….” The most bizarre stuff can happen in “real life,” and we hesitate to place it in fiction." In fact I have a blog post with the title, When Truth is Stranger than Fiction. For me the process is, theme (which is women's nineteenth century occupations) then do research on the subject, and somewhere in the process of the research the characters and mystery plot come, with their own introduction of meaningful themes. But this also works for contemporary stories, and my science fiction stories. Subject of interest to me, preliminary research, and the characters and plot and sub-themes follow, often in very unexpected ways. For anyone interested in how this works for me, here is the link to another post about this process: https://hfebooks.com/when-truth-is-stranger-than-fiction-by-m-louisa-locke/