This is an outstanding volume.

Here’s the story

I posted a review of a book co-edited by Annie Finch. I declared it to be THE book about creating poetry. And it is a wonderful book. Then Ms. Finch—Dr. Finch—showed up here on the Unschool and left a comment to let us know she has a more recent book. I’m so glad she did. I asked to review a copy. When it arrived and I cracked open the box, I had that sense of opening a Gift.

It’s taken time to read, and I’m left hungry to dig deeply into it in the New Year. I’d like to invite you to join me in that work, and we’ll open discussion threads. More on that shortly…

Poetry is not for poets alone

I often speak to the strengthening nature of working outside your chosen (or most “natural”) genre.

But poetry makes a difference in writing in any form, and brings with it a particular joy. It’s enlivening to work with words, to feel them in your hands as you put them together, to hear their sounds in your soul, to absorb until words then emerge from you in ways that surprise.

For those of us who make a living from writing fiction and nonfiction, or who expect or hope to, poetry can take us to a place of creating that is free of that (oft miserable!) money/work piece. Poetry can be a place to go slowly, and to be reminded why we are here. A touchstone.

And poets, beginning and experienced, will find sustenance in A Poet’s Craft. The beginner will find the layer they need; the advanced will find the equivalent of beyond a graduate writing program.

Annie Finch has held significant positions teaching poetry, writing and teaching for decades. In our world of ageism—no, I will not back off in saying that!—it’s such a pleasure to hold in hand the work of Experience and Time. There is no substitute for time, thousands of hours spent living a love. We know this as writers. The material in this volume is not the snips of expertise lobbed at us from a youngster (for writing, that means under the age of fifty). This level of craft comes into being only when one has lived and practiced a number of decades.

A Poet’s Craft opens with “This book distills into a few hundred pages a lifetime of hearing, memorizing, reciting, reading, imagining, conceiving, scribbling, dictating, dreaming in, writing, typing, word-processing, revising, proofreading publishing, perusing, discussing, parsing, analyzing, criticizing,scanning, editing, teaching, reviewing, translating, and loving poetry.”

That’s a thorough list of what writers do. Write long enough, and you will do all those pieces. (Maybe not typing.)

She’s a little off with one thing though: the book is not “a few!” It is more than 600 pages in length, and has a rich appendix of pages of scanned poems. (If you’ve wondered how to find the meter in a work, here are answers; there is also a sister-volume to this that takes an even closer look.)

She writes that the aim of the book is to be “stimulatingly idiosyncratic and usefully comprehensive.”

The table of contents is 23 pages, which makes it easy to find landing places, and roam the comprehensive.

Terror

This needs to be addressed.

I think—after having taught poetry to elementary-aged children as well as grad-school adults—about the terror of poetry. After coming up with my own approach for a grade four class, the teacher asked if she could keep a copy of my materials. She shared with me how much she not only loathed poetry, but doubly loathed the teaching of it.

Since that experience, I am aware that far too many people have inherited such loathing from teachers who themselves have been taught by the same; such things have a way of flowing from one generation to the next.

I’m aware that in writing about this book, and its creator, it all may sound overwhelming for those who still feel the inherited-loathing! But please keep your very self open; this volume opens with a close read of “Little Miss Muffet.” Yes, that Miss M—of Mother Goose. Stay with it, work your way through the pages here, the readings and suggested books list, and you will find yourself in a place of deep knowledge. (The Miss Muffet piece is quite perfectly placed to lead in.)

Joy

The examples of poetry are a trove, from early verse to contemporary, each shared with thought, and enough to spend months with; you’ll have a list of poets you want to explore further.

There’s a first-century work, addressed to Charon, mythical Greek ferryman who carries souls to the land of the dead. This poem gave me shivers. (Check out page 174.)

Finch writes of how poets read. And about how to allow a poem to read you, a key piece. She writes of what it is to memorize poems, to immerse—you inside poem, and poem working on the cellular.

She speaks to the etymology of words as generative, inspiring, and speaks of her collection of dictionaries from around the globe, and how to make use of them. She writes of “word music”—an entire chapter is devoted to this. Weeks could be spent with this chapter alone. She addresses the modes of poetry—lyric, narrative, dramatic.

She does the expected taking apart of elements—lines, syntax, stanzas, so much more. But goes further. She subtitles the pages on syntax as “words in order and disorder;” I appreciate this throughout: the re-thinking, re-approaching. Too, the chapters with such titles: “What if a Much of a Which of a Word-Music” and “Stop Making Sense,” and sections with sub-headings like “stretching and breaking language.”

Rhyme is broken down into more types than I’ve seen elsewhere. Beyond the breakdown of “perfect” and “slant,” there is “apocopate,” “mosaic,” “anagram,” and more. Overwhelming? I suspect it might feel overwhelming if you are merely reading through; this is a book that asks you to stop, and write. Take out your notebook and play, it begs of you, with all the ask of a dog and a fine day out of doors.

The poetic forms included and discussed have a breadth—from the sonnet (and “reclaiming the sonnet”) to the blues, the paradelle—again, comprehensive. In writing of free verse, Finch includes “Six Types of Free Verse.” There’s the “gosa,” which uses distinct lines from others’ works, and the DIY “nonce” form—create your own. Again, reading in depth, with time, and practice. I’m hardly touching on what is here. But hope to be giving you a taste.

As in the earlier work I reviewed, these are not simplistic descriptions of forms; each poetic form has ways of breathing with and around its parameters, and this is part of the whole. Nothing is written in stone. We are given the stone-like qualities of each form—what is set—and also shown where is the give. The section on the “value of repetition” is gold.

Nothing is easy. Nothing is impossible. The respect for the work that Poetry asks of us in creating is evident.

The last section of the book is about publishing and sharing one’s work. And it opens with words on revising. Wise words on revising, considering focus and play, “big” changes, “small,” all followed by a checklist.

Each chapter closes

with a few pages of “Questions for meditation or discussion,” “Quotes,” and “Poetry practices” (divided into ‘group’ and individual).

Examples:

In “Questions…” here: (p. 57) “William Stafford, who had a habit of writing a poem every day no matter what, used to say that the key to writer’s block is simply to lower one’s standards. What do you think of this idea? What kid of writing practices do you tend to be following, at the times when you feel best about your writing?” (My emphasis on this last piece—so revealing to self.)

In “Quotes”: (p. 482) “Without form, how could words bear the weight of emotions?” (Maya Sharma)

In “Poetry practices”: (p.482) “Stanza Sampler. Take one of your unrhymed poems and break it up into at least four different lengths of stanzas. You might try it in couplets, tercets, quatrains, seven-line stanzas, and irregular-length stanzas. Notice the differences it makes to the poem. Are you inspired to make different kinds of revisions for the different poems?

You might want to keep a journal, even just for these end-of-chapters pieces, with a separate one for the poems you are working on. Depending on how you work.

Finch quotes to leave with you…

“I usually know when I am writing a metaphor; often it is preceded by a kind of questioning, reaching feeling, as I wonder how best to put something—and then the metaphor is resolved by an “aha” feeling, a sense of having finished and moving on.” p. 175 (My emphasis on the ‘questioning, reaching’—which is exactly the feeling of so much of writing.)

“…rhythmical language is processed in a different part of the brain from prose and normal speech…” p. 205

On abstraction: “The modernists’ obsession with image has had a healthy influence on poetry-writing; beginning writers are often prone to abstraction… Still, I think contemporary poetry is narrowed in scope and weakened in effect, nearly a hundred years later, by taking [William Carlos] Williams’ dictum too literally…” p. 146

On revision: “All the [revision] tactics depend on a certain amount of objectivity, and time is the best provider of objectivity that I know…” p. 588

~~~

Here is the link to order A Poet’s Craft, directly from Annie Finch’s shop at bookshop.org.

~~~

In the coming year

I’d like to savour this book in 2023. With the TOC as it is, I’m open to roaming exploration. I’m hoping a number of you purchase the book, and study—that is, mark up! Scribble all over! Dog ear and chew corners! Then let’s talk about particular pages or poems or forms—we can let free our collective curiosity. Post poem efforts. Let the sweat show.

I’m hoping you’ll consider joining me in this, whether or not you think of yourself as “poet.”

I will post a loose discussion thread within the week. We don’t need to do anything in any formal way for these December days. But feel free to comment or offer thoughts on the discussion thread. And in January we can begin with a monthly thread. I’d like to progress slowly, thoughtfully.

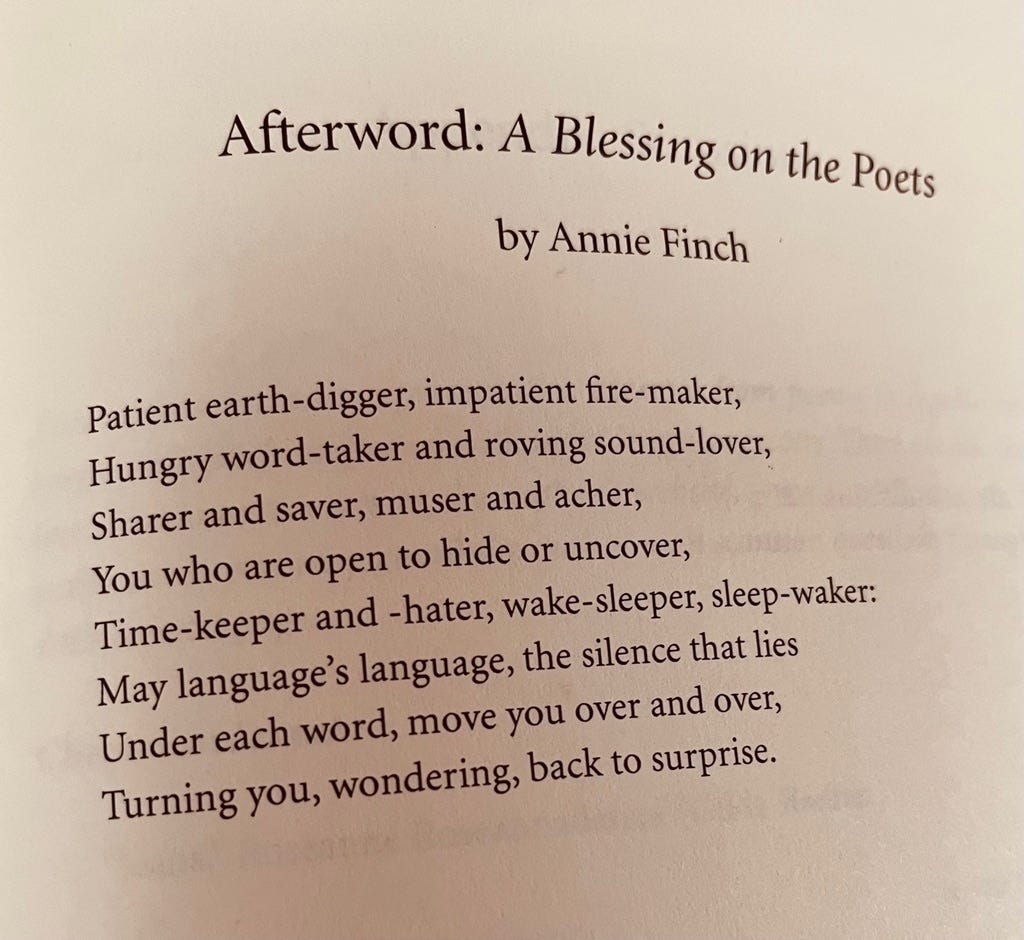

Finch closes with a blessing—

This sounds like a most wondrous book! I can relate to the loathing of poetry, at least in one way. As a small human poetry meant reading Edward Lear's limericks and the poems by Shell Silverstein, and I saw it as a small, funny story that rhymed, which I liked.

And then I went to The School in grade 10 English, where they made you stare your eyeballs out at a poem that did not rhyme and we had to follow the rules from a "How to Read a Poem" worksheet. Then we were supposed to dissect the poem for about thirty minutes to figure out what it was really about. Usually it ended up being something about some depressed grown-up, to relate to the curriculum's theme of universal doom (e.g. Romeo and Juliet, etc.)

And then I went to regular college and took some poetry writing courses there and had to unlearn everything from grade 10 about poetry, in the sense that poetry is supposed to be about playing around with words and not writing stuff to confuse people on purpose, and that was a most happy thing to discover.

Just knowing that there is a title called "What if a Much of a Witch of Word-Music" in it makes me plot to go read this book. Thank you!

This is exciting. This may be my first and only resolution. (I'd like to say there are more, but one good one is plenty.) I love that quote about metaphor. I've only just recently (this morning) became awayr of that joy, so it is very happenstance to have read about it this evening